Research demonstrates that there is a direct influence between socioeconomic status, cognitive growth, and language development in the early years.

Even before a child is born, it is communicating with the world around it. Sensitive to the sound of human voices, a child can recognize its mother’s voice in the womb as well as turn its head toward someone who is talking to it. They are like sponges absorbing every sound, pattern, and human interaction as it analyzes and builds the complexities needed for language development. Indeed, there is plenty of research to show just how important communication between parents and children is during the first three years of life for cognitive growth and language development.

Scientific studies have indicated a correlation between the amount of words children hear in their first couple years and their level of verbal intelligence. As early as 2 months, babies can begin exhibiting language as pleasurable “cooing sounds” as well as some consonant sounds such as “g” and “k”. Their language development is built on imitation and pattern recognition, whereby at 6 months, a baby’s babbling mimics the rhythm of conversational tones. Talking to babies strengthens their neural pathways and allows them to form an understanding of how language works. Repetition helps to reinforce the learning of words and discern native languages.

Researcher Patricia Kuhl’s TED Talk, The Linguistic Genius of Babies, sheds light on the phenomena of a baby’s language acquisition. She describes them as “citizens of the world”, intently listening and keeping statistics on sounds and languages they hear. The crucial moment of learning occurs right before their first birthday, when they start to understand the dominant language(s) they are intended to speak. According to Kuhl, when it comes to learning language, “babies and children are geniuses until they turn seven, and then there’s a systematic decline.”

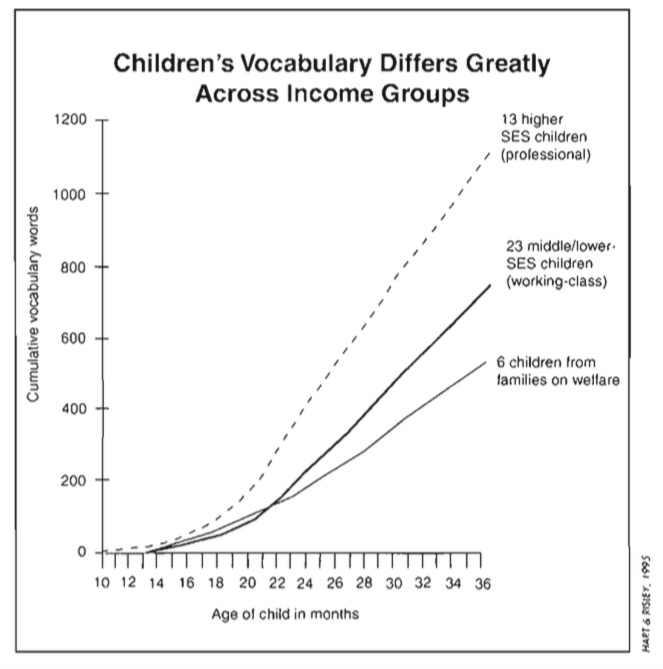

Betty Hart and Todd R. Risley’s seminal research in their work, The Early Catastrophe: The 30 Million Word Gap by Age 3, depicts a staggering state of communicational discrepancies between parents and children divided along socioeconomic lines. Their study included 42 families of different socioeconomic backgrounds: 13 high-income families, 10 middle socioeconomic families, and 6 families on welfare. They conducted monthly hour-long observations of each family beginning at 7 months until the age of 3, and in total recorded 1,300 hours of conversations. What they discovered was stunning. By the age of 3, children from high-income families were exposed to 30 million more words than children whose families were on welfare. Furthermore, 86 to 98 percent of a child’s vocabulary was derived from its parents’ vocabulary, including vocabulary growth and patterns of interaction.

Most prominently, this study highlighted how much each family within their respective socio-economic status exposed their child to language experience. On average, a child on welfare had half as much experience (616 words) as the average working-class child (1,251 words) and less than one-third experience than that of a child of a professional family (2,153 words). In a 100-hour week, that’s 215,000 words for the professional family, 125,000 words for the working-class family, and 62,000 words for a child on welfare. Extrapolated over a period of 4 years, the study indicated that a professional family exposed their child to 45 million words, a working-class family to 26 million words, and a child on welfare to 13 million words. Nuanced subtleties in the types of conversations families had within their SES also show stratified differences. Affirmative or encouraging words vs. prohibitions existed within each group:

-Professional families: 32 affirmatives to 5 prohibitions per hour; 6:1 encouragements to prohibitions; first 4 years: 560,000 more encouragements than prohibitions

-Working-class families: 12 affirmatives to 7 prohibitions per hour, 2:1 encouragements to prohibitions; first 4 years: 100,000 more encouragements than prohibitions

-Families on welfare: 5 affirmatives to 12 prohibitions per hour, 1:2 encouragements to discouragements; first 4 years: 125,000 more prohibitions than encouragements

Growth in a child’s vocabulary directly correlated with the child’s vocabulary level by the time they were in the 3rd grade (roughly 9-10 years old). Hart and Risley concluded in their study:

“Behaviorally, infancy is a unique time of helplessness when nearly all of children’s experience is mediated by adults in one-to-one interactions permeated with affect. Once children become independent and speak for themselves, they gain access to more opportunities for experience. But the amount of diversity of children’s past experience influence which new opportunities for experience they notice and choose.”

The current state of affairs concerning children’s language experiences are both a challenging issue to address and an exciting forefront to explore. As they talk to their children, not only do parents solidify the unique and intimate relationship they have with them, but their children also receive cognitive benefits that may last a lifetime. Parents and their children should look at these conversational opportunities as a win-win situation.

It is beneficial to parents from lower socioeconomic backgrounds to receive training for how to read, talk, and sing with their infants and toddlers to foster language. That’s exactly what The Latino Family Literacy Project trains teachers to do with parents at schools.